SWORN SISTERS: In conversation with Xiao Lu, Rose Wong, and Dr Geoff Raby

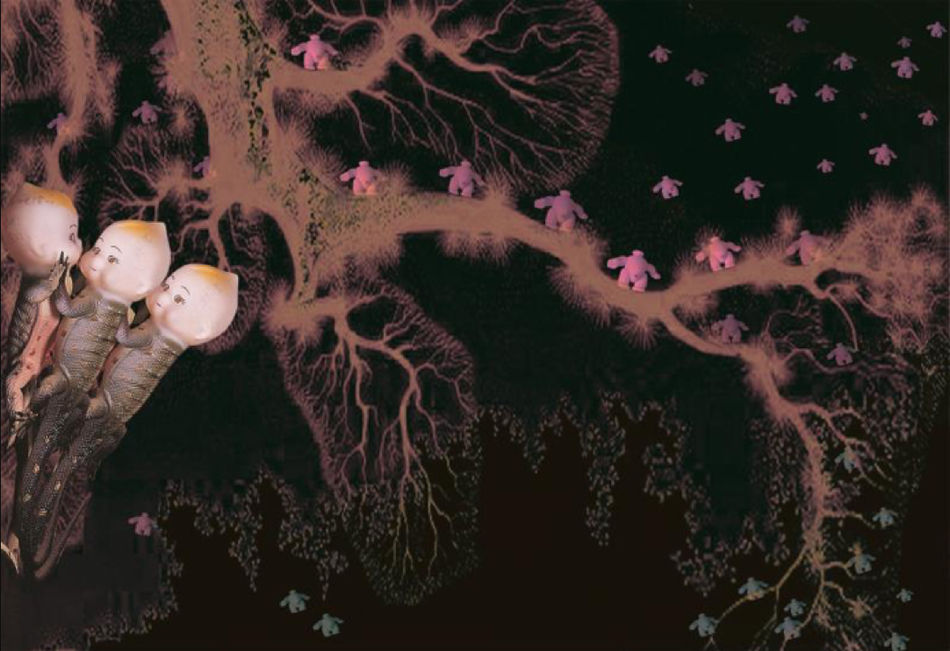

ByWendy Fang"A Long March" (2014) by Chen Qing Qing 陈庆庆. Image courtesy of Vermilion Art.

Delving into the world of contemporary Chinese women artists, Vermilion Art's recent exhibition, Sworn Sisters 女書, unravels deeply personal messages about these artists' time, nationality, and gender. The exhibition also grapples with what it means to play the role of a 'woman' in present society, but more importantly, it also reveals the performance of women artists dancing in an industry that is still heavily dominated by men. Demonstrating raw female experiences, each of these nine artists refuse to be silenced and therefore seek to undermine any preconceived ideas about what it means to be a woman, an artist, and most importantly, a woman artist today.

The following interview was conducted and features promininent contemporary Chinese women artists, Xiao Lu 肖鲁 and Rose Wong 王滢露, and former Australian ambassador to the People's Republic of China and curator of the exhibition, Dr. Geoff Raby.

Wendy Fang: Since this is your first time curating a show, why have you chosen to represent contemporary Chinese women artists? More importantly, what is the significance of their gender (woman), time (contemporary), and nationality (Chinese) in today's current context?

Dr Geoff Raby: First of all, I was invited by Yeqin from Vermilion Art to curate a show. She only shows contemporary Chinese art and part of the connection between Yeqin and myself is that I am a big collector of Chinese contemporary art. So, it made sense that it is Chinese contemporary art that I curate and certainly at the Vermilion gallery.

Why I chose women is mainly because I have a lot of friends amongst Chinese contemporary female artists, but more importantly, I was looking for what would be the themes, signature and take-out from the exhibition. I hit upon the idea that it would be great to have an exhibition of really edgy, challenging work from Chinese female artists that take on the stereotypes of Chinese women - to challenge the stereotypes of being passive, submissive, subservient and being wives, homemakers, even tiger mothers perhaps. Instead, I wanted to show artists, who represent the reality of contemporary Chinese women in terms of their complexity, creativity, and energy. The one thing that all the works in the collection have in common is that they are not conformists.

"Life, light parcel" (2005) by Chen Qing Qing 陈庆庆. Image Courtesy of Vermilion Art

Wendy Fang: Why have you chosen the title - Sworn Sisters 女書 and what is the meaning behind it?

Dr Geoff Raby: The title really came from Yeqin and we had a couple ideas floating around as to how we would title the exhibition. Yeqin knew about this ancient Chinese language that was only spoken by women and she had this idea that the artists in the collection, all being contemporary Chinese artists, had a language of their own that they would communicate with each other. It's a very nice way to tie the whole show together.

Wendy Fang: Could you talk a little about why you think Sydney has only now had an exhibition like Sworn Sisters? Given the geographical proximity of China and Australia, why do you think contemporary Chinese female artists are only now receiving international interest the way their male counterparts were given long before?

Dr Geoff Raby: I think that is an international phenomenon. I have a different perspective of China because I lived there for eleven and a half years and I think about things a little bit differently, but there has almost been no female contemporary group show of Chinese artists anywhere in the world. I have a friend of mine, who owns WhiteBox gallery in SoHo, New York,. He sent me an email saying, "Congratulations on the show, we have never done this in New York. Sydney is clearly ahead of New York in showing Chinese contemporary art". The Chinese contemporary art scene is a very male dominated art scene and yet the female artists are fantastic and there are so many of them. Chinese women nowadays can have an independent life and be economically secure and they don't need the support of a husband.

I think, more than anything else, I really hope the show may have or can achieve an influence over the conversation about Australia's relationship with China. Maybe it doesn't change the conversation, but at least the tone. No one who goes to see this show can possibly look at it and leave their prejudices and stereotypes the same. If you go there, with even the slightest open mind, it would change anything about China.

"Xie Yue" from the series GIRLS (2015) by Luo Yang 罗洋. Image courtesy of Vermilion Art.

Wendy Fang: I want to go back to the exhibition title again. Xiao Lu and Rose Wong - what does the significance of Sworn Sisters and this secret language between women mean to you as contemporary Chinese female artists?

Xiao Lu: For me, the title is just a name for the group show. The more important aspect of this exhibition is that it is the first all-female artist exhibition in Sydney, Australia.

Rose Wong: For me, when I read it I didn't quite understand what it meant. However, after Yeqin explained it to me I thought about how many female artists in China are still working underground with many hidden layers. There is this idea of a secret language between contemporary Chinese female artists where you have to go against the rules of mainstream society.

Wendy Fang: Xiao Lu, you mention the significance of the having the first all-female exhibition in Sydney, could you perhaps expand on the similarities or differences you have encountered since experiencing the artistic community in Sydney compared to Beijing?

Xiao Lu: At the moment, China has very strict censorship laws that govern their society and consequently their artists. So, when coming to Sydney from these sorts of circumstances in China it is very liberating.

Rose Wong: I agree with Xiao Lu. The control is getting tighter and tighter in China. Even with the number of new museums, galleries and art institutions opening, for me, the contemporary art scene in China is evaporating.

Wendy Fang: Could you explain what you mean by "evaporating"?

Rose Wong: It is like boiling. There are still a lot of artists, a lot of collectors, and many things happening. Whereas, I think Sydney's arts scene is more developed and calmer. People are more observant, laid back, and reserved.

Xiao Lu: An example of China's strict censorship was last year at the '中国百年女性展' (Woman and Era: 100-year China Women's art exhibition) at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing. Works by contemporary artists from the 80's and 90's were taken out of the show for no reason.

Wendy Fang: Was this experience similar to the 1989 China/ Avant-Garde exhibition at the National Art Museum of China, where it was shut down by Chinese authorities almost two hours into the exhibition?

Xiao Lu: I think in 1989, China's art scene was probably more liberating because most people did not truly understand the term 'contemporary art'. Even myself, at the time, I did not fully comprehend what it meant to be a 'performance artist'. Therefore, the limitations of getting into the National Art Museum of China was very small because even the government officials did not fully understand what 'contemporary art' entailed. Everyone was curious about it and as artists, we were hopeful because it was a new and fashionable thing. Upon reflection, I believe the 89' contemporary Chinese artists were enthusiastic, honest, and eager to express themselves in ways that were impossible before. However, I also believe that the same passion of these artists will not return because it was a special time in which these idealists were born.

Rose Wong: I think for Xiao Lu's era, they were very pure and so eager to open their doors and access the Western knowledge. Today, however, our society is so complicated and focused on capitalism (even though we say we are a communist state) that we are more concerned with economic growth. Therefore, there is a lot of attraction towards the Asian art market.

Xiao Lu: I think being an independent artist in this day and age is very difficult. There are all sorts of high pressure temptations from politics and economics. In order to become an independent artist, you must reject these temptations and be tolerant of such pressures in order to navigate the world with a clear mind-set.

Wendy Fang: Could you expand on that sentiment a little further? Do you think in order to be a successful contemporary artist today, you need to take on political and social concerns of the time or concentrate on channelling your own personal ideas and feelings into your work?

Xiao Lu: My process in making art is often based on my own personal feelings. Although, I also believe that no matter what your intentions are for the work, there will always be some embodiment of social and political meanings. It is unavoidable. However, for me personally I do not approach my work with one particular political or social concern. That being said, once you receive external pressure, the work's internal state will naturally change. That is why I like to empty my mind and make it zero when I start a new work. I try to eliminate other influencing factors, so that I can be highly receptive to the world we currently live in. In order to make sense of my surroundings, I need to experience and understand many things and then find what is most relevant and poignant to me before expressing it through my art.

Rose Wong: I really agree with Xiao Lu because there are a lot of Chinese contemporary artists that talk about socio-economic and political concerns. However, as an artist, I feel that you have to start from your own personal experiences because you have to consider why that particular incident matters to you and the way that it affects your life and other people's hearts. I think nowadays, nobody is brave enough to talk about individual expression. There is too much focus on the economic, social and political concerns of the world. But for the individual, artists have to be brave enough to be independent and be true to themselves. It does not mean that we do not care about societal issues because of course we will always care to some extent since we are living in it.

"Polar' (2016) performance by Xiao Lu 肖鲁. Video Courtesy of Vermilion Art.

Wendy Fang: Xiao Lu – you mentioned in your Tate interview with Monica Merlin, “the same piece of work created at the same time and at the same exhibition” can have different critical receptions based on the way it is talked about. Either it is praised for its socio-political concerns, or, condemned for its lack thereof. Why do you think that is?

Xiao Lu: That is probably because it was the same artwork, but in a different location. For me, every time I create an artwork I never repeat my previous artworks. I must experience something new, challenging and exciting in the face of producing a new work. There may be some faint similarities between my artworks, but never any obvious overlapping elements. Sometimes, when I create a work, I have minor regrets because of the way it has been received, but that is just life. You should seek to acknowledge that regret, let it go, and move on to create another work because it is normal to not feel completely satisfied and in control of every piece of work. This is the sort of attitude I hold towards my own life.

Rose Wong: I think for me, I would repeat some of my works if it involves audience participation. However, like Xiao Lu, I would not repeat the same work too many times.

Wendy Fang: What about your performance piece, Floral Pursuit 2015, where you first performed it in Beijing and then recently again at the opening of Sworn Sisters, here in Sydney?

Rose Wong: The first performance was done in 798 Art Zone in Beijing and people did not really understand what was happening, so they were giving flowers to me very quickly and actively because they were very curious. However, here in Australia, particularly those who attend many openings, they were more knowledgeable about performance art and were therefore quite reserved when it came to giving me roses because they knew how it may be harmful to my body. I think what Xiao Lu said is very therapeutic for me because I felt a small sense of regret after performing Floral Pursuit in Sydney because I felt the reactions I received back in Beijing were more instinctual and straightforward.

"Floral Pursuit" (2015) performance by Rose Wong 王滢露. Video courtesy of artist.

Wendy Fang: I know that both of you use your own bodies to navigate your experiences and express yourself through performance art. Why do you think it is important to use the female body, and even more so, your own body to convey your art?

Xiao Lu: For me, I think it is because I can control my own body and my works are highly personal so the outcome is often based on my own interactions with the audience.

Wendy Fang: Does it have anything to do with performing as a woman?

Xiao Lu: In some ways yes, for example, Money Laundering 2015. This performance used tools that were used by women for thousands of years to wash clothes. This performance could only be executed by a woman, even though the material that was being washed was money, which is a very masculine object.

Also, Wedlock 2009, where I married myself without a groom, the work has to be performed by a woman. Therefore, it depends on the work's concept and often I find that you need a woman's body to perform it because it is personal to a woman's experience of the world.

"Money Laundering" (2015) performance by Xiao Lu 肖鲁. Image courtesy of the artist.

"Money Laundering" (2015) performance by Xiao Lu 肖鲁. Image courtesy of the artist.

Wendy Fang: Is it important to still use women collectives and group shows, like Sworn Sisters, to strengthen their cause – or should we strive for women artists to be seen for their art and not their gender?

Xiao Lu: I think when I am creating a work I forget about whether I am female or male. However, from a societal perspective, I will always support and protect women artists. This is because in mainstream society, a contemporary woman artist's position is very weak and many famous exhibitions (both domestic and international) are taken up by men. Therefore, no matter what societal labels are placed on me, I will always support women artists and promote activism.

Rose Wong: I think we definitely need to acknowledge that we are female and that we are experiencing the world as a female. We start from our hearts and our personal experiences, which are contained within this gender. So, why should we escape from this female gender? I think this escapism is subordinate to patriarchal systems, where you have to 'de-feminize' yourself to be equal to men. I don't think that is possible and also not the right way.

I also completely agree with Xiao Lu. Of course, we are conscious of our female body as a material, but we are also using different kinds of material. For example, I use copper in my sculptures and mix it with painting. Copper is a very masculine material, so I think that it is important to have exhibitions, like Sworn Sisters, because we have to be conscious about what a 'female' looks like and not escaping by saying, "we are not female". Even as female artists, we internalise a lot of these ideas about ourselves, but we also have to constantly reflect upon and be conscious of them in order to break down these stereotypes.

"切开 5" (2016) by Rose Wong 王滢露. Image courtesy of Vermilion Art.

Wendy Fang: Finally, what does the label 'contemporary Chinese artist' mean to you? Do you think it is accurate or a Euro-centric label placed upon Chinese artists after the 1980's as a way to analyse your work from a Western lens?

Xiao Lu: I feel as though the 1980's, for many aspiring young Chinese artists, was a period of time where China was looking towards the West with a sort of blind admiration. A lot of people now see these artists as 'imitators' of the West because a lot of the artworks produced were in response to and a reflection of Western art movements and styles.

I knew a Bulgarian painter and modern tapestriest, called Maryn Varbanov, who taught at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou, China where I was studying in their oil painting department. At that time, we only knew of one medium and one technique, which was oil painting. As a student there, I would read a lot of Western art books and was very confused about what 'contemporary' art meant. Varbanov explained to me that contemporary artists can “用一切手段去表达你想说的” (use all means to express what you want to say). Meaning that I do not have to restrict my materials to oil paints and canvas.

I think China does not have the same art ecosystem as the West, where there is a proliferation of philosophers, artists, writers and critics that have historically engaged in challenging debates that led to where contemporary Western art is now. On the other hand, our artistic narrative was dismantled during the Cultural Revolution and so to use the term 'contemporary Chinese art', it is clearly from the perspective of a Western art discourse that is trying to make sense of our Chinese art history.

Despite this, it is not my concern how others label my work. All I want to focus on is my own creative processes and ensure that it is an authentic reflection of my own personal artistic practice. Everything else is irrelevant.

Special thanks to Yeqin Zuo, Gallery Director of Vermilion Art, for giving me this special opportunity to conduct this interview.

The exhibition ends on the 14th of July, 2018.

Any views or opinions in the post are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the company or contributors.